THE BUKAVU SERIES

The invisibility of southern researchers

Although their expertise is vital to the research process, researcher-assistants from the Global South are all too often treated as mere data collectors, and erased from the final products of the very projects they make possible. In this image, Tembo Kash depicts this experience of erasure by showing us a Congolese researcher who, upon glimpsing himself reflected in the “Academic Mirror,” finds that he has completely vanished, leaving behind only his research briefcase. Academia, it seems, wants the data he has collected, but has no interest in him as a researcher in his own right. Many authors in the Bukavu Series grapple with this issue in their texts – perhaps none more so than Élisée Cirhuza in his essay “Taken out of the picture? The researcher from the Global South and the fight against ‘academic neo-colonialism’” and Aymar Nyenyezi Bisoka in “Can silent voices speak? When power relationships govern the conditions of speech.”

Information is not for free

Paying research participants for information is generally frowned upon and thought to put the quality and veracity of the data at risk. As such, project managers from the Global North tend not to include such payments in their project budgets. Yet on the ground, Congolese researchers often find themselves in delicate situations with local authorities, and even community members, who view information sharing as a transaction. In “When you become Pombe Yangu (My Beer): Dealing with the financial expectations of research participants,” Jérémie Mapatano describes the complexities involved in confronting respondents’ demands for remuneration in the field. Meanwhile, in their joint essay, “In the presence of white skin: the challenges arising from people’s expectations when encountering white researchers in the field,” Élisée Cirhuza Balolage and Esther Kadetwa Kayanga examine, among other things, how the presence of white researchers can heighten participants’ expectations of financial compensation.

Traumatic experiences in the field

Many of the essays in the Bukavu Series deal with the psychological toll that work in a conflict zone can take on researchers over time. In “When the backpack is full: the omertà surrounding the psychological burdens of academic research,” An Ansoms writes that this toll is further augmented by a culture of silence in academic circles. Few spaces exist in which researchers can show vulnerability and speak openly about the traumas they witness or experience during their work. Instead, people are expected to shoulder their psychological burdens silently and present a brave face to their colleagues. In this satirical image, Kash shows a Congolese and a foreign researcher being urged to believe that the human bones they have encountered in the field are just bonobo skeletons – rather than the obvious traces of a recent atrocity. Ansoms ends her essay with an impassioned call for a shift away from a culture of stiff-upper-lipped silence, towards one of openness and mutual support.

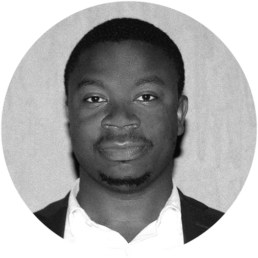

Undermining female researchers

In her essay “The challenges facing female researchers in conflict settings,” Irène Bahati explores the specific challenges local women researchers face during fieldwork in the DRC. In this image, Kash has chosen to expand on one of the issues Bahati raises – that of the social backlash Congolese female researchers face from people (and at times even other women) who expect them to prioritise domestic duties over professional aspirations.

Valuing data over life

Throughout the Bukavu Series, writers draw attention to the fact that local researchers and research assistants in the Congo are often valued only for the data they collect. They are rarely given the opportunity to participate as full partners in the research projects they carry out. Worse still, in many cases, even their physical safety is treated as an afterthought, so long as they supply the data their Northern collaborators need. This is one of the issues Alice Mugoli Nalunva touches on in her essay, “Between Passion and Precarity: the work of a researcher in the DRC.” In the cartoon presented here, Tembo Kash illustrates this theme with a depiction of a Congolese researcher who has just escaped a capsized boat. When the researcher makes a phone call to report what has happened, he finds that his boss cares only about the safety of the project data.

No protection for kidnapping, no provisions for ransom

Project managers based in the Global North often fail to recognise that work in conflict zones can put local researchers on the ground at tremendous risk. This disregard for Congolese researchers’ safety is a recurring theme in many of the Bukavu Series texts. In their collaborative essay Work Without Pay? A critical look at the contracts and lived experiences of local researchers in the DRC, Élisée Cirhuza, Irène Bahati, Thamani Précieux Mwaka and An Ansoms argue, for example, that research contracts not only fail to provide equitable pay for Congolese researchers, but also neglect the safety of these local researchers during their work in the field. Meanwhile, in “Surviving Intimidation: When having your research challenged upends your life as researcher”, Bosco Muchukiwa shows how, even when working on their own projects, researchers in the Global South face dangers that their counterparts in the North do not have to contend with. In this cartoon, Kash illustrates Cirhuza et al.’s critique by depicting a white project manager who tells his kidnapped research assistant that there is no budget available to pay his ransom and rescue him, but that arrangements can be made to retrieve the data he collected.

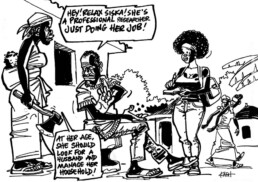

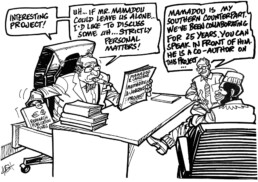

Power imbalances in academic writing

The issue of academic and intellectual erasure is one of the most persistent themes of the Bukavu Series. Time and again, series contributors relate their experiences of being relegated to the position of data collector despite the abundant expertise they have to offer, and the manifold ways in which they are indispensable to the research process. In this cartoon, Kash highlights this phenomenon with the depiction of a young researcher presenting his boss with the extensive research and analysis he has conducted for a project, only to be told that his business is simply to hand off the data he collected and go home. In “‘They stole his brain’: The local researcher – a data collector, or researcher in his own right?”, Stanislas Bisimwa Baganda asks why local researchers tend to be excluded from publications when so many research projects would be completely infeasible without their input as facilitators and contributors.

Similarly, in her essay “‘Donor-Researchers’ and ‘Recipient-Researchers’: bridging the gap between researchers from the Global North and Global South”, Judith Buhendwa Nshobole argues that researchers in the Global North have a responsibility to make knowledge production more equitable by including Southern researchers in all stages of a research project. Meanwhile, in “‘These Phantom Researchers’: What of their visibility in academic publications?”, Bienvenu Mukungilwa points out that excluding local researchers from the publication process leads to a lost opportunity for all members of a research team. Finally, in “We Barely Know These Researchers from the South! Reflections on Problematic Assumptions about Local Research Collaborators”, Emery Mudinga challenges researchers in positions of power to interrogate their preconceived notions about their research assistants and collaborators, arguing that this is the first step toward addressing and rectifying the issue of rampant intellectual erasure in academic research.

Imposing western agendas

In this image, Kash draws attention to the phenomenon of project managers from the Global North ignoring local expertise, and instead unilaterally dictating how local researchers should pursue their research. Here, an NGO worker hands a Congolese researcher a “Specification Note” that instructs him on how he should carry out the project, and what conclusions he should draw – before he has even begun his research. In his essay, “‘A research assistant is just an implementer’: the argument in favor of involving local researchers in project design”, Vedaste Cituli Alinirhu reflects on what is lost when local researchers are excluded from the process of designing research projects and instead expected to merely implement the ideas of others. Writing in a similar vein in “The NGO-ization of Academic Research”, Pierre Basimise Ngalishi Kanyegere makes the case that by dictating research objectives from the top down and ignoring local expertise, NGO staff do a disservice not only to local researchers, but also to their own research objectives. In “Escaping Big Brother’s gaze in research in the Global South”, Joël Baraka Akilimali shows that similar dynamics play out in academic circles. Finally, writing in agreement from the Northern perspective, in “Can collaborative research projects reverse external narratives of violence and conflict?”, Koen Vlassenroot argues that the existing structure of North-South research collaborations needs to be overhauled in order to give local researchers a greater voice in the study and analysis of the DRC.

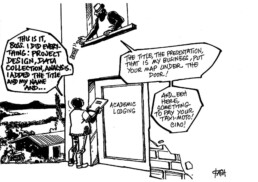

Dangers, threats and ethics of perceived espionage

Data collection in conflict zones or insecure settings is an exceptionally delicate process, requiring resourcefulness, flexibility, and a nuanced understanding of local contexts. In “Navigating Armed Conflict Zones”, Josaphat Musamba gives readers an introduction to the wide range of challenges involved in carrying out research in a conflict zone, and describes some of the creative strategies local researchers employ to confront obstacles in the field. In “He’s hiding under his hat! Going in disguise to collect data in the field,” Précieux Thamani Mwaka, Stanislas Bisimwa Baganda and An Ansoms describe some of the specific challenges Congolese researchers encounter when working with respondents who are suspicious of their research. They go on to discuss the solutions researchers find to these challenges; as well as the risks they incur, and the ethical grey zones they enter when they sometimes choose to disguise the fact that they are researchers. Meanwhile, in “When an Armed Guide is Imposed on You: Navigating Research in a Conflict Zone,” Eric Batumike Banyanga demonstrates what can happen to a researcher when suspicions reach a critical point, recounting his own experience having to conduct fieldwork under the “protection” of an armed guide. In the accompanying image, Tembo Kash shows how quickly tensions can escalate between researchers and respondents, if suspicions arise between the two parties.

Manoeuvring tight deadlines

While local researchers and research assistants carry out the bulk of research in the Congo, researchers based in the Global North continue to dictate the designs, timetables, and goals of most research projects in the country. Thus, the people designing the projects are often out of touch with realities on the ground, and may impose unrealistic expectations and demands on their colleagues in the South. Researchers in the South, meanwhile, often feel unable to challenge these demands due to entrenched imbalances in power, resources, funding, etc. As Kash shows in this illustration, such pressures may at times force local researchers to make ethically questionable decisions in their work. For a candid and perceptive exploration of these dynamics, check out Esther Kadetwa’s essay “Reliable data? The pressure to deliver, versus the complexities of the field,” and Élisée Cirhuza’s “Remunerating researchers from the Global South: a source of academic prostitution?”

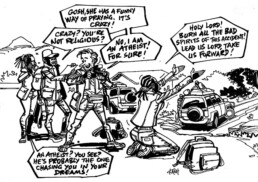

Acknowledging cultural differences

Conducting fieldwork as part of a multicultural team creates many opportunities for learning and exchange. At the same time though, such collaborations can occasion cultural misunderstandings that lead to tensions within a team. In his essay, “Lost in translation? Managing cultural differences in the face of risk in the field”, Dieudonné Bahati Shamamba recounts some of his own experiences working in mixed Congolese and European research groups, and reflects on ways for collaborators to build a better sense of understanding across the cultural divide. Here, Tembo Kash depicts a disagreement about the significance of religion arising within a multicultural research team after a traumatic event. The image is loosely based upon an anecdote in Shamamba’s essay.

Objectively researching ‘home’

Several writers in the Bukavu Series reflect on the trauma, fear, and guilt they experience in the course of their fieldwork. Unlike researchers from the Global North, local researchers and research assistants in the Congo are often connected to the communities they are asked to research. While foreign researchers may be able to maintain a degree of detachment from the situations they study in the field, local researchers often do not have this emotional luxury. In her essay “The egocentricity of field ethics: questioning otherness, decency and responsibility,” Anuarite Bashizi grapples with the guilt and distress she and other Congolese researchers experience when confronting their informants’ suffering in the course of fieldwork. Similarly, in “Epistemological rupture, detachment, and decentering: requirements when doing research ‘at home’” Francine Mudunga examines the ethical challenges local researchers face when their work requires them to assume a degree of emotional distance from respondents in communities with which they themselves may have ties. Meanwhile, in “Waiting for the morning birds: researcher trauma in insecure environments”, Thamani Mwaka Précieux recounts how, as members of conflict-affected communities, local research assistants sometimes even find their own lives at risk while conducting research.

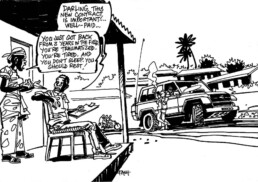

Emotional pressure

In his essay “Research, or Adventure? The lived experiences of researcher assistants”, François-Merlan Zaluke Banywesize highlights the ways that unrealistic demands from project funders and managers in the Global North lead local researchers on the ground to feel overwhelmed and burnt out. Here, Tembo Kash poignantly illustrates this issue by depicting a discussion between a Congolese researcher who feels pressured to take on a new project, and his wife who is deeply dismayed by the physical and emotional toll the work is taking on him.

Navigating male-dominated spaces

Although they had both already written blog posts for the Bukavu Series, as the project unfolded, An Ansoms and Irène Bahati found that an important theme remained under-examined in the Series’ exploration of the emotional, security, and ethical challenges researchers face in the field. Feeling that the specific experiences of female researchers still required more attention, the two women collaborated on an essay about this issue. In “When the room is laughing: from female researcher to researcher-prostitute,” Ansoms and Bahati bear witness to the harassment and intimidation women face in the field as a result of their gender, describe the strategies female researchers must use to navigate such treatment, and call on the academic world to recognise and begin to address the particular vulnerabilities of women researchers in the field. In this image, Tembo Kash deftly adapts several of Ansoms and Bahati’s anecdotes into a single image showing a standard research exchange that takes a threatening turn when two soldiers layer sexual innuendo into their responses to a female researcher’s inquiry.

Towards equitable collaboration

The Bukavu Series is, in large part, an exploration of the wide range of moral and ethical challenges that arise in the course of collaborations between researchers from the Global North and Global South. In his essay “‘Businessisation of Research’ and Dominocentric Logics: Competition for Opportunities in Collaborative Research,” Godefroid Muzalia shares insights from eight years of work in North-South research collaborations, often as the “Southern coordinator” for projects whose terms and funding are dictated from the North. Meanwhile, in “Umoja ni nguvu: towards more equitable collaborative research,” Josaphat Musamba and Christoph Vogel reflect together on their personal experience building an equitable partnership (and friendship) over the course of nearly a decade of joint research in the DRC. In his nuanced illustration for these two blogs, Tembo Kash depicts a North-South research partnership based on genuine mutual support and respect. Yet he shows us that such partnerships are only one part of the solution to the persistence of the colonial mindset in knowledge production. For full decolonisation to occur, we must also confront the wider academic structures in which prejudiced assumptions about researchers from the Global South remain the norm.

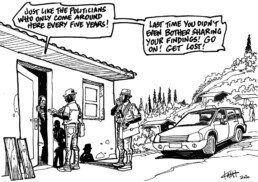

The researcher-respondent dynamic

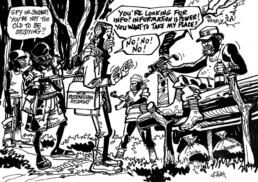

Several essays in the Bukavu Series highlight the extractive nature of research in insecure settings, critiquing the tendency of research teams to collect data from communities without ever following up again to inform respondents of their studies’ findings. While researchers from the Global North generally return to their home countries after a project, their local assistants and collaborators remain on the ground and may continue to cross paths with former respondents. As such, local researchers must confront the frustrations and research fatigue of respondent communities in a way that researchers from the Global North are rarely compelled to. In their essays “‘Hold on; we’re still thinking it through.’ When will we get a report on your findings?” and “’Give Me Back My Words’: reflections on a forgotten aspect of participant follow-up” Christian Chiza Kashurha and Isaac Bubala Wilondja each convey their own frustrations at not being able to provide respondent communities with findings from the studies they participate in. Both writers point out that Congolese researchers often lack the power to hold project managers from the Global North accountable to the communities in which research is conducted. They therefore each call on Northern researchers to themselves reflect more critically on the process of knowledge production, and to consider who such knowledge is ultimately intended for.

Meanwhile, in her essay, “‘Come back later.’ – ‘On what day?’ – ‘Just, come back!’”, Irène Bahati documents the exasperation that respondents in over-researched communities feel at repeatedly being asked to participate in studies whose impact they never get to see. Similarly, in “The ‘Researcher-Glutton’: Data collection in insecure settings in the Global South”, Espoir Bisimwa Bulangalire shows how exasperation in respondent communities can grow into resentment and even hostility toward local researchers, who are often the face of research projects on the ground, despite having little sway over the trajectory of the studies that they work on. Here, Tembo Kash uses an image of a fraught conversation between a Congolese research assistant and a would-be respondent to illustrate the interconnecting themes explored by all four of these essays.

Copyright © 2022 by bukavuseries.com and Tembo Kash. All rights reserved. This website, images, content or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher. For more information contact: intdev.crp@lse.ac.uk